Polygons and Metallic Means

Introduction

From Polygons, Diagonals, and the Bronze Mean by Antonia R. BuitragoThe Metallic Means Family (MMF) was introduced in 1998 by Vera W. de Spinadel [1998; 1999]. Its members are the positive solutions of the quadratic equation $x^2-px-q=0$, where the parameters $p$ and $q$ are positive integer numbers. The more relevant of them are the Golden Mean and the Silver Mean, the first members of the subfamily which is obtained by considering $q=1$. The members $\sigma_p$, $p=1,2,3 \ldots$ of this subfamily share properties which are the generalization of the Golden Mean properties. For instance, they all may be obtained by the limit of consecutive terms of certain "generalized secondary Fibonacci sequences" (GSFS) and they are the only numbers which yield geometric sequences:

$$ \ldots, \frac{1}{{\sigma_p}^3}, \frac{1}{{\sigma_p}^2}, \frac{1}{\sigma_p}, 1, \sigma_p, {\sigma_p}^2, {\sigma_p}^3, \dots $$

with additive properties

$$ 1 + p \cdot \sigma_p = {\sigma_p}^2 $$ $$ {\sigma_p}^k + p \cdot {\sigma_p}^{k+1} = {\sigma_p}^{k+2} $$ $$ \frac{1}{{\sigma_p}^k} = \frac{p}{{\sigma_p}^{k+1}} + \frac{1}{{\sigma_p}^{k+2}}, \mbox{ } k = 1,2,3,\ldots \ . $$

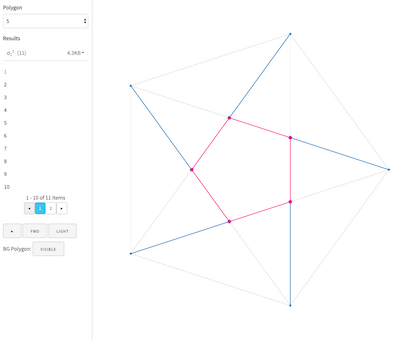

In Polygons, Diagonals, and the Bronze Mean, Antonia Redondo Buitrago demonstrates that the bronze mean does not appear as a side to diagonal relationship in a regular polygon. Yet there still remains the question of whether or not metallic means appear as a ratio between line segments like in the pentagon, Figure 1.

Logic

Figure 2

Figure 3

Let there be a regular polygon with $n$ sides and vertices and a circumradius of 1. Connect each vertex pair with a diagonal $d_i$ and let $P_{d_i}$ be a set of intersection points between $d_i$ and each other diagonal:

$$ P_{d_i} = \{ p_1, p_2, p_3, \ldots, p_j \} $$

where $j$ is the total number of intersection points for a given diagonal $ d_i$.

Let $L_{d_i}$ be the set of lengths between pairs of points in $P_{d_i}$:

$$ L_{d_i} = \{ \overline{p_1 p_2}, \overline{p_1 p_3}, \ldots, \overline{p_{j-1} p_j} \}. $$

For a regular polygon, only a single vertex and its diagonals are needed due to rotational symmetry.

For a vertex, the number of diagonals required to encompass all possible lengths of a regular polygon is $ \lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor $ due to reflectional symmetry. Reflectional symmetry reduces the number of diagonals by half because diagonals opposite each other across a line of symmetry have the same set of line segments; even-sided polygons also include the diagonal that is the circumdiameter.

Taking figure 2 as an example,

$$ L_{d_1} = L_{d_6},\ L_{d_2} = L_{d_5}, \ L_{d_3} = L_{d_4} \text. $$

And for figure 3,

$$ L_{d_1} = L_{d_7},\ L_{d_2} = L_{d_6},\ L_{d_3} = L_{d_5},\ L_{d_4} = L_{d_4} \text. $$

Then, the complete set of lengths for a regular polygon with $n$-sides is

$$ L_n = \bigcup\limits_{i=1}^{\lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor} L_{d_i} \text. $$

Then to test if a metallic mean $\sigma_p$ exists as a ratio of lengths in $L_n$, we find the intersection between $L_n$ and $ \sigma_p \cdot L_n $:

$$ \begin{array}{rl} M_{\sigma_p} = & L_n \cap (\sigma_p \cdot L_n) \ = & \{ x \in L_n : \exists l \in L_n (x = \sigma_p \cdot l) \} \text. \ \end{array} $$

If the intersection $ M_{\sigma_p} $ is not empty then the metallic mean exists as a ratio of lengths.

Example

Let's take a look at a simple example, the pentagon, which has an established relationship with the first metallic mean, the golden mean $\varphi $. The pentagon has the characteristic that any diagonal is representative of all diagonals so we'll use the blue diagonal from figure 1.

Let $L_5$ be the complete set of line segments for a pentagon

$$ L_5 = \{ \overline{AB}, \overline{AC}, \overline{AD}, \overline{BC}, \overline{BD}, \overline{CD} \} $$

and the lengths are

$$ L_5 = \{ 0.44902, 0.72654, 1.17557, 1.90211 \} \text. $$

So to test for the first metallic mean, we multiply $L_5$ by $ \sigma_1 $, where $ \sigma_1 = 1.61803 $,

$$ \sigma_1 \cdot L_5 = \{ 0.72654, 1.17557, 1.90211, 3.07768 \} $$

and we find that all but one is a member of $L_5$:

$$ M_{\sigma_1} = \{ 0.72654, 1.17557, 1.90211 \} \text. $$

Additionally we can test for the fourth metallic mean by multiplying $ L_5 $ by $ \sigma_4 $ ($ \varphi^3 $), where $ \sigma_4 = 4.23606 $,

$$ \sigma_4 \cdot L_5 = \{ 1.90211, 3.07768, 4.97979, 8.05748 \} $$

and we find that only one is a member of $ L_5 $:

$$ M_{\sigma_4} = \{ 1.90211 \} \text. $$

Program

install required packages: pip3 install -r requirements.txt

usage: main.py [-h] [--dps DPS] [--buffer BUFFER] [-s] n mean_id

positional arguments:

n # of sides for regular polygon

mean_id metallic mean to test for

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--dps DPS decimal precision [default: 50]

--buffer BUFFER decimal precision buffer [default: 5]

-s, --show_matches show matches

examples:

python3 main.py 5 1

python3 main.py 8 2

python3 main.py 13 3The program is written in Python3.7 using mpmath for arbitrary-precision. mpmath is required because double-precision has an insufficient number of significant digits to account for the very tiny variations in lengths which result in false positives.

mpmath is set to 55 decimal-places, an arbitrarily sufficient number, with 5 decimal-places as a buffer to account for minor cumulative computational errors. Then the computed mpmath values are converted to decimal string literals with 50 significant digits allowing for string comparisons of relatively precise decimal values.

lib/utils.py

import mpmath as mp

# nstr() is a mpmath function that converts an mpf or mpc

# to a decimal string literal with n significant digits.

def getkey(val): return mp.nstr(val, SIG_DIGITS)

# return metallic mean for specified n

def mmf(n): return (n+mp.sqrt(n*n+4))/2lib/vector2.py

import mpmath as mp

from .utils import getkey

class Vector2(object):

def __init__(self, x=0, y=0):

if mp.almosteq(x, 0): x = 0.0

if mp.almosteq(y, 0): y = 0.0

self.x = mp.mpf(x)

self.y = mp.mpf(y)

def __add__(self, other):

return Vector2(self.x+other.x, self.y+other.y)

def __sub__(self, other):

return Vector2(self.x-other.x, self.y-other.y)

def __mul__(self, other):

if isinstance(other, Vector2):

return Vector2(self.x*other.x, self.y*other.y)

else:

return Vector2(self.x*other, self.y*other)

def __str__(self):

return '<Vector2 x=%s y=%s>'%(str(self.x)[:10], str(self.y)[:10])

def __repr__(self):

return self.__str__()

def __hash__(self):

return hash((getkey(self.x), getkey(self.y)))

def __eq__(self, other):

return mp.almosteq(self.x, other.x) and mp.almosteq(self.y, other.y)

def cross(self, other):

return self.x*other.y - self.y*other.x

def dist(self, other):

return (self-other).len()

def dot(self, other):

return self.x*other.x + self.y*other.y

def len(self):

return mp.sqrt(self.dot(self))lib/linesegment.py

import mpmath as mp

class LineSegment(object):

def __init__(self, start, end):

self.start = start

self.end = end

self.vec = end-start

def intersect(self, other):

numerator = (other.start-self.start).cross(other.vec)

denominator = self.vec.cross(other.vec)

if (not numerator or mp.isnormal(numerator)) and mp.isnormal(denominator):

ratio = numerator/denominator

return self.vec*ratio + self.start

return None1. Generate the vertices of the polygons and connect each pair of vertices with a diagonal.

main.py

# n is polygon size

theta = 2*pi/n

# calculate vertices

vertices = []

for i in range(n):

x = cos(theta*i)

y = sin(theta*i)

vertex = Vector2(x, y)

vertices.append(vertex)

# generate diagonals

diagonals = []

for i in range(n):

for j in range(i+1, n):

v1 = vertices[i]

v2 = vertices[j]

diag = LineSegment(v1, v2)

diagonals.append(diag)2. For each diagonal calculate and collect intersection points between itself and other diagonals. Then within the same iteration calculate and collect distances (lengths) between pairs of points in a dictionary using a consistent key for the mpmath value.

main.py

# calculate line segments lengths

lengths = dict()

for i, diag in enumerate(diagonals[:n//2]):

# find intersection points

points = set()

for other in diagonals[i+1:]:

# find the intersection point between diagonals

point = diag.intersect(other)

# ensure point lies within unit circle

if point and point not in points and abs(point) <= 1:

points.add(point)

# calculate lengths for pairs of points on the same diagonal

if len(points):

points = list(points)

for j, point1 in enumerate(points):

for point2 in points[j+1:]:

dist = point2.dist(point1)

key = getkey(dist)

if key not in lengths:

lengths[key] = dist3. Iterate over the set and multiply each length by a metallic mean and test to see if the resultant value is contained in the length set.

main.py

# test for specified metallic mean

count = 0

for k,l in lengths.items():

key = getkey(mean*l)

if key in lengths:

count += 1Metallic mean selection

We could test every polygon with every metallic mean but eventually the number of lengths grows too large to compute by hand or a modern desktop computer. So it is prudent to find a method for determining appropriate metallic means for polygons or conversely, a method for identifying prospective polygons for metallic means.

Now back to the definition of a metallic mean. They are the positive solutions of the characteristic equation $x^2 - px - q = 0 $ when $q := 1$ and $p$ is a positive integer. Then the quadratic equation is

$$ x^2 - px - 1 = 0 $$

and the quadratic formula to compute the means is

$$ \sigma_p = \frac{p+\sqrt{p^2+4}}{2} \text. $$

Selecting appropriate polygons to test for metallic means $ \sigma_p $ appears to be related either to the discriminant, $ p^2+4 $, or the simplified form of the radical $ \sqrt{p^2+4} $. metallic means that are a power of a lower mean appear alongside their lower counterpart.

In the case of $ p=1 $, the golden mean $\varphi$, the discriminant is 5 and the simplified radical is $ \sqrt{5} $, associating the metallic mean with the pentagon and polygons with a number of sides that is a multiple of 5. For $p=4$, $ \varphi^3 $, the discriminant is 20 and the simplified radical is $ 2\sqrt{5} $ which is also associated with the pentagon and polygons with a number of sides that is a multiple of 5. For $p=11$, $ \varphi^5 $, the discriminant is 125 and the simplified radical is $ 5\sqrt{5} $ but does not appear until $n$ is a multiple of 10 or 15. Similarily $p=29$ appears when $n$ is a multiple of 20 or 30 and $p=76$ appears when $n$ is a multiple of 30.

In the case of $ p = 3 $, the discriminant is $ 13 $ and the radical is $ \sqrt{13} $, associating $ p = 3 $ to the tridecagon.

In the case of $ p = 6 $, the discriminant is $ 40 $ and the simplified radical is $ 2\sqrt{10} $. The associated polygon is a 40-gon.

In the case of $ p = 8 $, the discriminant is 68 but the associated regular polygon is a heptadecagon ($ n=17 $), which relates to the simplified radical $ 2\sqrt{17} $.

* As of writing this, I have been unable to determine values for $n$ when $p$ is 7,9 or 10 for $ p \leq 10 $.

Visualization tool

Results

| $p$ | Radical | $n$-gons | Trigonometric expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $$ \sqrt{5} $$ | 5x | $$ 2\cos\frac{\pi}{5} $$ |

| 2 | $$ \sqrt{8} $$ | 8x | $$ \tan\frac{3\pi}{8} $$ |

| 3 | $$ \sqrt{13} $$ | 13x |

Simplified (Wikipedia)

$$ 8\cos\frac{\pi}{13}\cos\frac{3\pi}{13}\cos\frac{4\pi}{13} $$

Original $$ 2\cos\frac{\pi}{13}\left(\sin\frac{2\pi}{13}\csc\frac{3\pi}{13}+1\right) $$ |

| 4 | $$ 2\sqrt{5} $$ | 5x | $$ 8\cos^{3}\frac{\pi}{5} $$ |

| 5 | $$ \sqrt{29} $$ | 29x |

Simplified (Wikipedia)

$$

128\cos\frac{\pi}{29}\cos\frac{4\pi}{29}\cos\frac{5\pi}{29}\cos\frac{6\pi}{29}\cos\frac{7\pi}{29}\cos\frac{9\pi}{29}\cos\frac{13\pi}{29}

$$

Original $$ \frac { \sin\frac{19\pi}{29} - \frac{1}{2}\csc\frac{19\pi}{29} ( \cos\frac{25\pi}{29}+1 ) - \sin\frac{25\pi}{29} \sin\frac{3\pi}{29} \csc\frac{20\pi}{29} } { \sin\frac{25\pi}{29} \sin\frac{5\pi}{29} \csc\frac{21\pi}{29} - \sin\frac{16\pi}{29} \sin\frac{\pi}{29} \csc\frac{7\pi}{29} } $$ |

| 6 | $$ \sqrt{40} $$ | 40x | $$ \frac { \sin\frac{21\pi}{40} } { \sin\frac{7\pi}{8} - \sin\frac{5\pi}{8} \sin\frac{\pi}{40} \csc\frac{11\pi}{40} - \sin\frac{19\pi}{20} \sin\frac{9\pi}{40} \csc\frac{7\pi}{10} } $$ |

| 7 | $$ \sqrt{53} $$ | ||

| 8 | $$ 2\sqrt{17} $$ | 17x | $$ \frac{ \sin\frac{6\pi}{17} \sin\frac{7\pi}{17} \sin\frac{3\pi}{17} \sin\frac{12\pi}{17} } { \sin\frac{\pi}{17} \sin\frac{9\pi}{17} \sin\frac{4\pi}{17} \sin\frac{2\pi}{17} } $$ |

| 9 | $$ \sqrt{85} $$ | ||

| 10 | $$ \sqrt{104} $$ | ||

| 11 | $$ 5\sqrt{5} $$ | 10+5x | $$ 32\cos^5\frac{\pi}{5} $$ |

| 12 | $$ 2\sqrt{37} $$ | 74 | $$ \frac{ \sin\frac{8\pi}{37} \sin\frac{5\pi}{74} \sin\frac{13\pi}{74} \sin\frac{17\pi}{74} \sin\frac{31\pi}{74} }{ \sin\frac{11\pi}{37} \sin\frac{\pi}{74} \sin\frac{7\pi}{74} \sin\frac{9\pi}{74} \sin\frac{33\pi}{74} } $$ |

If anyone happens to identify 7, 9 or 10 please let me know at tellerm<at>protonmail.com or on Twitter @tellerm. Thank you.

References

[1] Vera W. de Spinadel. (1999). The Family of metallic means. Visual Mathematics 1, 3. http://members.tripod.com/vismath1/spinadel/

[2] Antonia R. Buitrago. (2007). "Polygons, Diagonals and the Bronze Mean", Nexus Network Journal 9: 321.

Links

- CYCLOTOMIC POINTS AND ALGEBRAIC PROPERTIES OF POLYGON DIAGONALS

Thomas Grubb, Christian Wolird